A History of Brockhampton Park

A reader view may be obtainable by clicking on the left end of the browser search bar.

Figure 1: Johannes Kip’s c. 1710 engraving.

The original Brockhampton Park house was built around 1640 for Paul Pert, Serjeant1of the Counting House2for King Charles I, a notable position at the time. He had been acquiring land since 1638, and the house is built on what was known as Ford Hey, formerly belonging to a Thomas Chandler. The whole estate amounted to about 80 acres and included what is now the Equestrian Centre across the lane to Winchcombe (then known as the Port Way). The original house comprised the two-by-two gabled portion on the southwest corner of the present building.

Pert died in Oxford in April 1643, bequeathing the house and its estate to his niece, Ann Skipwith, who married Ralph Dodwell, a yeoman3of Brockhampton. In 1691, the property passed via her son Paul to her grandson William Dodwell, later Sir William Dodwell. Dodwell, a London lawyer, also added lands over the years, diverting lanes and creating a park and tree-lined avenue on the east side, leading to the village across a canal channelling the headwaters of the River Coln. To the west, Sir William planted formal gardens and began a park.

Figure 1 shows an engraving of the estate made around 1710 by Johannes Kip (1653–1722). While Kip was known for his somewhat flattering approach to illustration, the house and canal beyond are shown correctly. This engraving was part of a larger contract for Robert Atkyn’s 1712 collection, The Ancient and Present State of Gloucestershire.

Figure 2: Original barley-twist downpipe.

On Sir William Dodwell’s death, the property passed to Anne’s great-granddaughter Mary Dodwell, Sir William’s only child, who later married the wealthy Thomas Tracy of nearby Stanway House in 1746. Mary Dodwell died in 1799, leaving no children and no will, and several people came forward to swear that they were Mary’s real heirs. The convoluted legal battle that followed between a half dozen claimants lasted several years, with victory finally going to three impoverished sisters whose family – the Timbrells – had once owned a small farm in the parish.

Meanwhile, a succession of tenants rented the house, one of whom was Charles Craven, who had been Governor of the Province of South Carolina in the American colonies (at the age of 29) from 1711 to 1717. He had a farm at nearby Puckham, as evidenced by a note, which another landowner, Walter Lawrence, made in his Boock of & at Sevenhamton, dating from 1737: ‘December ye 16th 1749 then Bought of Goufener Craven 1 Waging at £5=5s=0d’, the said ‘Goufener’ being Governor Craven and ‘waging’ a wagon.

When Charles Craven died in 1754, his widow, Elizabeth, retired to Brockhampton Park for a short time, before moving to a Craven family house near Kintbury in Berkshire. She was notorious as the ‘cruel Mrs. Craven’, of legendary meanness, a scheming woman who ‘starved her five daughters and treated them as servants’, although a ‘most courteous and fascinating woman in society’.4She is said to have been the model for Jane Austen’s protagonist Lady Susan Vernon, of Jane’s eponymous novella. Jane was a lifelong friend of a Martha Lloyd, one of Elizabeth’s granddaughters, and also a frequent visitor to other friends in Kintbury.5

On Elizabeth Craven’s departure, the tenancy was passed to her only son, the Reverend Mr John Craven, presumably more favoured than her daughters. From a survey performed as part of the legal battle for ownership, we know that by 1803, he was paying a rent of £65 per annum for the estate and a house whose roof leaked: ‘the wet comes in, in several Places’. He died in 1804, and among a succession of tenants was the Reverend Mr William Pearce, the master of Jesus College, Oxford, and Dean of Ely. One person, a certain Mr Stevens, never became a tenant; his application was refused on the grounds he never got up in the morning.

The ownership of Brockhampton Park had remained in the hands of the Timbrell sisters, and, in 1823, the last surviving sister, Mrs Rebecca Lightbourne, bequeathed the estate (sometimes called ‘Seavenhampton Park’ in some records, as on Kip’s map) to the Lawrences, who were lords of the manor of Sevenhampton. They quickly transferred the house and a large part of the estate to Rebecca’s Cheltenham solicitor, Theodore Gwinnett, in lieu of a large bequest she had made to him for his attentions to their successful legal pursuit of Brockhampton Park. He died shortly afterwards, and his trustees sold the house and estate to Fulwar Craven, Reverend John Craven’s son.

Figure 3: Fulwar Craven’s enlarged west facade.

Figure 4: Fulwar’s tower.

The new owner enlarged the house considerably, remodelling the west range, adding two further gables, extending the building to double its length northwards (Figure 2). He built the porch and a castellated turret as a top light for the upper floor (now over Flat 21; Figure 3). It is probable that it was he who landscaped the grounds, creating terraces near the house and making a lake out of the canal. He may also have built the west lodge.

After Fulwar’s death in 1860, Brockhampton Park passed to his daughter Georgina Maria Craven and her husband, formerly Goodwin Charles Colquitt-Goodwin (they both changed their surnames to Colquitt-Craven on marrying). In the years

Figure 5: The house in 1884.

1864–1868, they rebuilt the east range on a much larger scale around a substantial light well; the east wall bears the gryphon and crosslet arms of the family and the date of the work (Figure 4 shows the house in 1884). Kipshows a three-span bridge on his c. 1710 engraving, and it is likely that the existing finely carved bridge piers were built during the Colquitt-Craven period on the old foundations. Their son, Fulwar John Colquitt-Craven, a tragic figure, inherited the estate in 1889, but died 6 months later at the age of 41, allegedly of a broken heart, but more likely of drink. His wife, Sarah née Dillwyn, known as ‘Essie’, had deserted him and their five children three years earlier, absconding to South Africa with an impoverished Irish actor named Richard Packenham and causing a great scandal. Colquitt-Craven’s son, Lewis Fulwar John, who was only 16 when his father died, inherited the estate. The Craven years are commemorated in the name of the Brockhampton village pub – The Craven Arms.

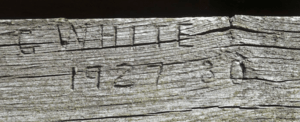

Figure 6: Graffiti or a true date?

Very soon after, around 1900, Lewis sold the house and land to the Yorkshire barrister Colonel Fairfax Rhodes, whose family fortune was based on stockbroking and coal mines. He was a cousin of the Cecil Rhodes who founded the colonies of Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. He roofed over the inner hall – which until then had been the light well – forming a two-storey Great Hall and had the plasterwork renewed in Arts-and-Crafts style. Rhodes built the summerhouse, added to the west lodge and, perhaps, re-built the timberwork of the bridge over the lake, adding a steel truss supported deck. The actual date of this work is unknown, but there is an inscription, ‘G. White 1927–30’ amateurishly chiselled into one of the timbers (Figure 5), which may be graffiti or the true date of the work. Rhodes’ initials can be seen on some of the older rainwater heads around the house and lodge (Figure 6).

Figure 7: Rhodes initials on the west lodge.

Rhodes probably hoped to establish a dynasty at the Park, but his much-loved only son, John Fairfax Rhodes, was tragically killed in the Boer War at the age of 25, in 1902.6 His first wife, Mary, died in 1915 and he later re-married (Mary Louisa Rhodes). He died in 1928. His second wife remained at Brockhampton Park until 1934. Both wives and his son are buried in the graveyard of Charlton Abbots church. Rhodes was a considerable benefactor to the village.

After the Rhodes years, the house went through a chequered period. During WWII it briefly housed part of the Cheltenham Ladies College; at the end of the war, it was a recovery home for soldiers; a country club/hotel for a time; and, later still, it became corporate offices, workshops and laboratories for the Cheltenham engineering firm of Dowty. Even during these diverse years, it retained some shreds of its earlier grandeur since its park to the west, now the

Figure 8: The White Deer herd.

Equestrian Centre, provided range for the only herd of white deer in Britain (Figure 7). A British Pathé News clip from the 1950s on YouTube (paste https://bit.ly/3cle4QR into your browser) provides a very dated cameo of the house and herd and reveals the return of another Dodwell descendant, David Dodwell. Surprisingly, though recent history, the years following the departure of the Rhodes family are not well defined and the shadowy owner who was David Dodwell’s father-in-law deserves research. It is certain that Brockhampton Park was offered to The National Trust at some point, but the offer was declined and it was finally sold to Barratt Developments, who converted it into the existing 21 flats. They also converted the estate buildings to the north into residences and sold off building lots along what is now The Mews. The house and remaining 8 acres of grounds continue to evolve and thrive in the care of its various owners and their voluntary Board of Directors.

David Cuin Giles Browne

Notes:

Figure 9: The main entrance and west lodge c. 1930

1. Sergeants at Law were an elite order of attorneys who had the exclusive privilege of arguing before the Court of Common Pleas (actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the King) and also supplied judges for both Common Pleas and the Court of the King’s Bench (one of the three divisions of the High Court of Justice).

2. Counting House; traditionally the office where the books of financial accounts and correspondence regarding demands for payment were kept.

3. A yeoman was a free man who owned his own house and land – likely a farmer, but not gentry.

4. Caroline Austen, Reminiscences, pp 7–9.

5. See a later article: ‘Brockhampton Park’s Austen Connection’.

6. See a later article: ‘Mishap at Klippan.’