Bridge Restoration

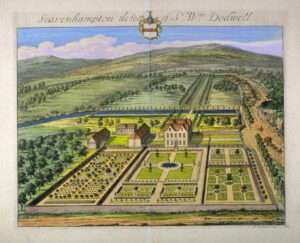

Fig 1: Kip’s engraving (c. 1710) depicting Brockhampton Park estate from the west.

A reader view may be obtainable by clicking on the left end of the browser search bar.

While the history of Brockhampton Park house is well recorded in various documents, this is not the case for the fine ornamental bridge over the lake. A three-span bridge is clearly shown in the Johannes Kip (1653-1722) engraving of the estate, which is dated ca.1710 (Fig 1), but this is the earliest record.

A visiting conservation architect judged the sculptural details on today’s piers supporting the bridge to be Victorian, which accords with the largest additions to the house (carrying the date 1863) by the Colquitt-Cravens, but it is probable the foundations on which they are based are much older.

Certainly, the bridge would originally have been timber and the steel structure supporting the deck that was removed when the substructure was replaced in 2016 had little physical connection to the timber arches or balustrade and was likely constructed in the early 1900s. The ‘beaked’ blocks supporting the balustrade may be the ends of original timber beams from the Victorian era. It is not known from when the timber arches date; one carries an amateurishly carved date of 1927–30.

Fig 2: Finely carved tops of the bridge’s piers.

Fulwar Craven, Georgina Colquitt-Craven’s father, probably expanded the original canal into the current lake and island. Kip shows the straight canal. The lake is effectively the headwaters of the River Coln, although the stream actually rises at Isenwell spring near Charlton Abbotts.

Like the house, the bridge is a Grade II Listed Structure on the National Register and, when subject to construction activity, the principles of ‘replacing like with like’ and preserving the ‘look’ and ‘character’ must be observed. By 2011, the bridge was in dire need of repair and at risk of at least partial collapse. Various attempts at repair had been either superficial, ineffective, positively damaging, or abandoned as too costly. As a Listed Structure, the local authority has a responsibility to ensure the bridge’s preservation and has the power to step in and oblige necessary repairs, which, in the event of even partial collapse, would likely cost much more than biting the bullet of a major upgrade while it was still standing. It was also obvious that the balustrade was in a dangerous condition, raising the specter of liability in the event of accidents to residents.

Fig 3: Corrosion of the original deck support steelwork

In 2011, a detailed examination of the bridge revealed severe corrosion of the steel substructure supporting the deck and impending instability of some of the timber arches, particularly at the east end. Following intensive study and discussions with the local Conservation Officer, a major contract was prepared to completely replace the old steelwork and support the timber arches and balustrade from a newly designed deck substructure. This was completed in 2016.

Fig 4: The new steel substructure in place.

Fig 5: The new steelwork also supports the arches and balustrade.

Fig 6: The scaffold and working platform erected for the substructure replacement.

Fig 7: A test section of the balustrade fully dismantled.

It was apparent that the cost of refurbishing the oak balustrade in accordance with the Grade II requirements would also be high, given the cost of materials, specialist skills and potential difficulties in executing the work. Having spent a great deal to replace the substructure and stabilize the arches, work on the balustrade had to be deferred for several years as other important projects took precedence. The time was spent in the search for a suitable contractor to undertake the work at a reasonable cost. It transpired that many firms were simply not interested in tackling the difficulties of the work or lacked the required skills. However, in 2019 a suitable contractor was located who would hazard a quotation to enable the required Section 20 to be formulated. He undertook one test section to assess the feasibility of a construction method and the hidden difficulties of the task, such as the extent of rot.

Fig. 8: Reconstruction

The contractor proved ideal for the work, possessing the necessaryspecialist joinery skills and the ability to adapt to, and deal with, the constructional needs of the job. After agreement on methodology with the Conservation Officer, he dismantled one of the worst sections and was able to provide an acceptable quote for the reconstruction. He established a temporary workshop in the gardeners’ shed, where the refurbishment of still viable components and the preparation of new parts took place. The reconstruction was satisfactorily completed by the end of 2020, despite difficulties imposed by the Covid pandemic. A second section is budgeted for the last half of 2021, with plans for other spans to follow on, year by year, until final completion in 2025. If finance becomes available earlier, then this timescale could be reduced, but in an ageing stone property there are many projects that lay claim to funds.

Fig 9: The rebuilt balustrade.

Fig 10: The finished balustrade will soon weather in.