Details, Details…

The official listing for Brockhampton Park in the Listed Buildings Registry (see ‘What is a “Listed” Building?’ in History) goes into a lot of detail about the features of the house, both exterior and interior. One paragraph refers to the rainwater downpipes on the south and east facades: “Several fine rainwater heads; barley-twist downpipe[s] with beast’s head on rainwater head[s] on south wall, 3 ornate rainwater heads with scallop shell motifs and lion’s head gargoyles on east front.” There is no record of when the rainwater goods were installed, but it’s fair to assume it was concurrent with the construction of that part of the house in the 1860s.

Beast’s head rainwater head on

south elevation.

Access box for cleaning.

Above: A rainwater head on the oldest part of the building, the southwest corner. It carries the initials PP, Paul Peart, for whom the house was built in 1641, and his coat-of-arms.

Scallop shell motif rainwater head on the east side.

Right: Access box on east side.

Far right: Original bracket

missing on the east side.

Andy Doyle displayed his breadth of talent by devising new fixing plates and accepting the work to remove the old ones and install the new. He adopted a stonemason technique of setting a threaded, stainless steel rod in the wall and fabricated new, stainless steel plates to engage with the downpipe’s existing, unbroken collars (below).

Forming the new, stainless steel brackets.

Fitting old and new brackets to the existing collar.

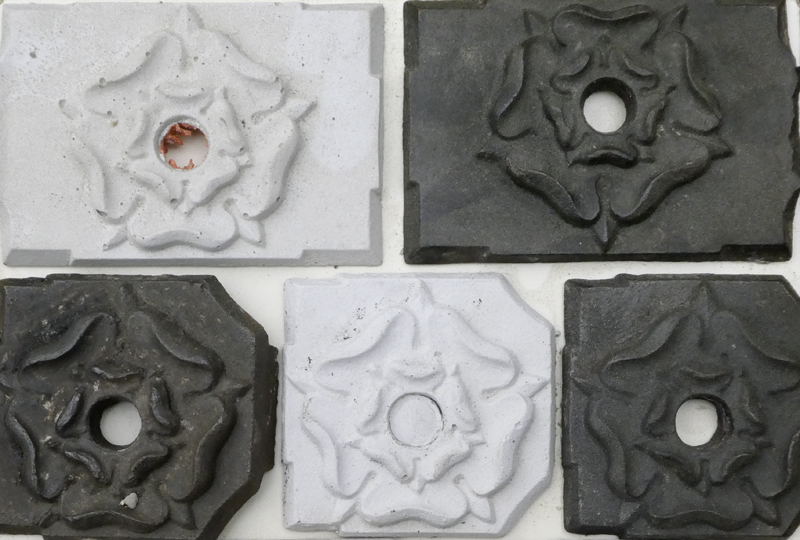

Peter Long (Flat 8) became interested in the work while, at the same time, bemoaning the loss of the broken brackets carrying the rose motif. That’s when a light bulb went on in his head. Peter is a ceramicist and he had the idea to produce moulded castings of the motif that could be bolted over Andy’s flat plates, using the same threaded rod. The fixing nut would become the centre of the rose. Initially, Peter intended to use clay, but Johan Pretorius sourced a fibre-reinforced concrete compound that would function the same way and be, arguably, stronger. Peter went to work making silicone moulds from cleaned brackets supplied by Andy and using those moulds to produce trial castings.

In the finished work, the new brackets are

indistinguishable from the old.

_________________________